Guest post by Christine Martin, Tufts University.

The potential for mobile technology to impact development has been researched and reported on in areas ranging from job matching services to financial inclusion. More and more development agencies are adopting mobile communications in their programmes in innovative ways. However, there is a lack of research on how mobile technology is being used to monitor and evaluate programs in the field.

Monitoring and evaluation, often abbreviated as M&E, is a popular topic among both academics and practitioners. While evaluation of programs can serve a number of purposes, including accountability to donors or transparency of use of resources, I am focusing here on M&E which is aimed at organizational learning that can be used to improve program implementation.

This type of M&E requires “adaptive management,” where the organizational culture is conducive to responding to information gathered through research. This level of learning presents a real challenge to organizations, and there are many problems with implementation even with a high level of commitment on the part of program staff. There are the difficulties surrounding the participation of beneficiaries, as well as a lack of understanding of how to make monitoring and evaluation useful to practitioners. Finally, both monitoring and evaluation are expensive, and often are sacrificed when budgets are tight.

I argue here that mobile technology can be integrated into M&E systems so that they are more participatory, useful, and cost effective.

An illustration of the challenge the new technology presents to organizations can be illustrated by looking at Femina HIP, a multimedia civil society initiative focused on sexual health based in Dar es Salaam. Femina HIP started to add an SMS feedback component to their health marketing materials, including pamphlets, radio campaigns, and television shows.

However, the reply was overwhelming and the organization found itself unprepared to deal with the volume of incoming responses. Unexpectedly, they found that SMS feedback helped to assess which marketing materials were the most successful at reaching the intended audience by the level of SMS feedback that each campaign inspired. However, they were not able to send a reply message every time, leading to the concern that citizens would lose trust in the campaign. In addition, the SMS responses were not being fed into a database which could help Femina process and analyze all of the information to draw conclusions about program changes.

I will here practically examine how an organization such as Femina Hip can use SMS technology to improve organizational learning. I'll delve into two examples: The well-recognized and widely reported success of the use of RapidSMS in UNICEF Malawi's Health and Nutrition Unit (PDF file), and Twaweza East Africa, an innovative new initiative that has recently begun to implement data gathering through SMS.

Involving participants in M&E

Within the monitoring and evaluation field, many people talk about participatory methods that aim to bring the voice of beneficiaries into the process. Participation can simply entail asking program participants to offer feedback or can actually involve the participants in designing the program and the indicators by which to monitor activities.

However, participatory methods are complicated to implement as they often require time and resources that the community cannot afford. Furthermore, “communities” rarely have a unified voice, and bringing them together to evaluate a program can exacerbate power inequalities within that society. As a result, evaluations can end up being interventions in and of themselves, unintentionally challenging gender or generational inequalities when the evaluation is not prepared for such intervention.

In theory, monitoring should increase communication at all levels, offering more opportunities for beneficiaries to offer feedback, and decrease the overall power imbalance that currently exists between beneficiaries, programmes, country offices, and donors.

There are few, if any, aid organizations that are actually implementing truly participatory monitoring practices at this point, with or without the use of SMS communication. There are many more examples of monitoring by key community members, most often community health workers (CHWs). Within the rapidly growing field of mhealth, organizations are providing CHWs with cell phones who are then able to communicate back with the NGO in real time. The data they provide is instantly fed into a database, through software provided by platforms including RapidSMS, for instance.

However, these applications have yet to implement SMS technology to give beneficiaries a voice in development projects. In communities where the majority of people own mobile phones, some of these problems can be addressed by asking simple questions about effectiveness of a program over SMS, making voting more private and giving members of a community a voice in the implementation of projects.

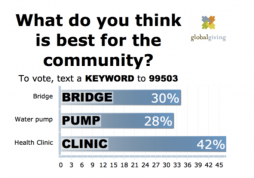

Dennis Whittle of Global Giving has developed an idea to improve decentralized aid delivery through SMS technology. He says: “Put up a billboard in each community saying what aid money is supposed to be going towards.”

The idea is that when a community receives a lump sum of money from an aid organization, a billboard will be placed in the center of town advertising the donation (reducing corruption) and giving options for how the money could be used. Each option would be assigned a different short messaging code, and each citizen could vote over text message, choosing which interesting: using text messages to take control out of the hands of aid agencies and to make aid truly community-driven (Whittle's 2009 presentation is here).

The example of Femina shows how SMS can start to bring voice to program participants. The high level of feedback received after Femina started to publish an SMS feedback number makes clear that their target audience is eager to ask questions and contribute to health programming.

The RapidSMS program in Malawi used SMS to help health workers monitor child nutrition in real-time, with the goal of improving the current paper-based system used by the government, which suffers from time-delay and lack of participation. The pilot project, run from January to May 2009, found that the use of SMS created feedback loops among multiple levels of stakeholders. Not only was the government receiving information about patients, this information was shared between various health service organizations. The understanding that they had a voice and the ability to trust that their feedback was being used gave community members and caregivers an increased sense of ownership in the surveillance program and increased incentives to participate.

Twaweza East Africa is attempting to integrate this increased level of feedback into its comprehensive M&E framework. The Twaweza model is not working directly with citizens, but with a variety of partners to create an ecosystem of change based on increased access to information. Through SMS data gathering which feeds directly into Twaweza's Infoshop, the Infoshop will be able to gain citizens' opinions of the work of Twaweza partners. Therefore, while partners are hearing from participants about specific program activities, Twaweza will be able to use citizen feedback to assess partnerships at a secondary level.

Of course, with direct citizen feedback, there is a need for validation. Feedback loops need to ensure that people who provide information are informed when and how that information is used to ensure trust and participation in the system. The RapidSMS Malawi system would automatically flag a reported height decrease in a child as an indicator that data was flawed, so that the relevant health worker could be contacted for verification. Twaweza will encourage citizens to participate in citizen monitoring surveys by sending a reply SMS with the exact day that the information will be published in the newspaper or announced through another form of media.

Another consideration is that although mobile coverage in Africa is rapidly expanding, it has not reached all areas or income levels. Organizations can address this by combining SMS feedback with other forms of communication, including radio, billboards, newspapers, and internet, as appropriate for reaching their target audience.

Utilization

There is no shortage of stories within the aid community of expensive monitoring programs that gather extensive data, which ends up being shelved and never used by project staff. In terms of utilization, mobile technology may have a more significant impact in monitoring than in evaluations, since mobile phones can aid with the ongoing collection of data to measure progress and results of program activities.

Monitoring is a vital component of evaluation, and if done correctly, can both increase accountability and inform policymakers on how to increase the impact of programs (Rossi 2007).

SMS is already being used by many programs to quickly communicate with participants about the delivery of services. Souktel, an organization working in Palestine, charges non-profits a small fee to be able to communicate with all of their beneficiaries through SMS. This service is being used by aid organizations including CHF International, which sends texts to families in Gaza with updates concerning the delivery of food and medical supplies (Korenblum 2008). This same concept can be used to gather a much wider range of data, which then be used to modify programs.

Using SMS to gather monitoring data can decrease the time it takes for an organization to receive feedback, allowing them to respond to problems or gaps in programming However, as seen in the case of Femina, even data collected through SMS can be under-utilized if systems are not in place to process it. The RapidSMS pilot project in Malawi was able to reduce transmission time from one to three months using a paper system to about two minutes – in other words, data was stored and available for analysis 64,800 times faster than with the previous paper system.

For an organization in the position of Femina, there are several open source, free software platforms available. RapidSMS, Frontline SMS and Ushahidi all offer their software for free and provide help online. RapidSMS and Frontline SMS are software platforms that enable two-way communication through SMS. Ushahidi is a crowdsourcing platform that provides the ability to map SMS data in real time. These are only a few of the many options available.

Still, organizations face a challenge in adopting the software for their unique needs, since each organization and context is different. Obtaining information about what tools work for specific needs and how can be difficult to obtain, understandably frustrating the efforts of many organizations. It seems that there is still a need for people that can advise on how an organization can develop a comprehensive strategy to fit their needs. In sum, “despite the enormous transformative potential of mobile phones, their impact on community development or the effectiveness of development organizations will depend on the capacity of stakeholders and beneficiaries to develop and engage with them, their attitudes, and practices (Beardon 2009).”

Cost Effectiveness of M&E

Evaluations are expensive: it takes time, money, and human resources to conduct surveys, focus groups, and site visits to understand if a program's activities are having the intended results. A comprehensive M&E system will gather baseline, mid-line, and end-line data to understand change in indicators over time.

Using cell phones to conduct surveys can decrease costs of this kind of data collection. Data collected through mobile phones or PDAs can be sent directly to a central database, reducing time and money spent on data entry. There are mobile platforms currently being developed to conduct mobile research in this way, such as Mobile Researcher, for example.

Use of mobiles will also lower other administrative costs, including the price of telephone calls or postal charges incurred through other methods of data collection. The UNICEF Rapid SMS program in Malawi found that data gathering through SMS replaced the previous time-consuming method of manual data entry and saved the cost of transporting paper forms and manually entering data.

Twaweza decided that the cost effectiveness of SMS could increase access to information to inform policy decisions in Tanzania. At this point, policy is informed by the Household Budget Survey (HBS), conducted every six years. Therefore, there is no evidence of a flawed policy until the following HBS six years later. Twaweza's Infoshop will use SMS to provide a reasonably low-cost method of collecting data on a much more frequent basis. In order to get a representative sample for data collection, it will still be necessary to incur the up-front cost of a household survey. The main reason for this includes the still low level of penetration of mobiles among the poorer households in Tanzania. However, the provision of cell phones to each household selected will allow follow-up surveys to be conducted through SMS. This will lower the cost tremendously, allowing data to be collected more frequently on a wider variety of issues.

It is worth noting that people may still need an incentive to reply to surveys, such a small amount of airtime delivered to their phone upon completion (Waluchio 2009).

Limits

As discussed, mobile phones have not penetrated all communities, and therefore not all communities will be able to participate in monitoring through SMS. This can be addressed by using a system of key informants, similar to community health workers. That said, mobile penetration is approaching one third of the world's population, and is growing every day. Because of the leapfrog nature of mobile phones, many developing countries have skipped other forms of communication, so that SMS represents the “lowest common denominator in terms of technology, thereby helping to assure the highest level of program participation (UNICEF 2009).”

Still, organizations need to do a careful context analysis of the availability of technology in the area in which they work, as well as the willingness of citizens to participate. This context analysis also needs to assess literacy in the area, which includes understanding the languages people speak, as well as their literacy level in relation to various technologies.

Although illiteracy presents a challenge, it also provides an opportunity. When Protege QV wanted to allow for increased communication among leaders of twenty rural woman's associations they trained each woman on using SMS, a skill they did not have previously. The women are now communicating not only within their local networks, but are also following-up with the head local office of the Protege QV, in order to access support materials, and gain further information on training and activities (Beardon 2009).

Researchers at Tufts University, University of Oxford and the University of California are working with Catholic Relief Services in Niger on a pilot program to teach literacy through SMS. The idea came from the results of a survey between 2005 and 2007 which found that some traders in the region were teaching themselves how to read in order to understand market prices provided by SMS. The researchers saw illiteracy not as an obstacle to mobile communication, but as an opportunity (Aker 2009).

It is also important to take into account the cost of text messaging, which is relatively inexpensive, but can still be a burden on poor households or small NGOs. One way to address this problem is through reverse billing of SMS, is available, so that the organization pays for the incoming SMS.

As with all forms of data collection, results of SMS data gathering will often have to be followed-up with site visits and more qualitative methods, including focus groups and interviews to truly understand the impact of programs. RapidSMS in Malawi found that the most significant limitation to scaling up the program was the lack of training and technical knowledge to actually process the data (although training community members proved to be relatively easy.)

Conclusions

Monitoring and evaluation of development programs can contribute to learning between organizations and the people they aim to serve, within organizations, and to the overall field of social change. Mobile technology has the potential to increase learning on all three of these levels, since it is more participatory, useful, and cost-effective than current methods of data gathering. As more organizations begin to use mobile technology for learning, their experiences should be documented and shared in order to understand how mobile technology can be used most effectively to improve M&E of all types of social change programs.

References:

Aker, J. Project ABC: Using Cell Phones as a Platform for Literacy and Market Information in Niger (2009)

Bearden, H. How mobile technologies can enhance Plan and partners work in Africa. Guide prepared for Plan (2009).

Church, C. and Rogers, M. Designing for Results: Integrating Monitoring and Evaluation in Conflict Transformation Programs. Washington DC: Search for Common Ground (2006).

Bush, C. Technoserve Rwanda, Interview (2009).

Engel, P., Carlsson, C. and A. van Zee. Making evaluation results count: Internalising evidence by learning. (ECDPM Policy Management Brief no. 16). Maastricht : ECDPM (2003).

Fabian, C. UNICEF, Presentation at Africa Economic Forum, Columbia University (2009).

Korenblum, J. Souktel, Talk at The Fletcher School and ongoing private communication (2009).

Rossi, P.H. and H.E. Freeman, H.E. Evaluation: A Systemic Approach. (6th Ed.) California: Sage Publications (2007) Chapter 6.

Waluchio, B. Interview (2009).

About the author: Christine Martin is a graduate student at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, where she is focusing on understanding the role of both technology and monitoring and evaluation in making development aid more effective. She has experience in monitoring and evaluation for the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) and Twaweza, a Tanzanian-based non-profit. While at Twaweza, she explored how a civil society organization can use mobile technology to improve organizational learning and increase access to information throughout East Africa.

Photo courtesy Global Giving.

Post new comment