Editor’s Note : In this article, guest contributor Paul Currion looks at the potential for crowdsourcing data during large-scale humanitarian emergencies, as part of our "Deconstructing Mobile" series. Paul is an aid worker who has been working on the use of ICTs in large-scale emergencies for the last 10 years. He asks whether crowdsourcing adds significant value to responding to humanitarian emergencies, arguing that merely increasing the quantity of information in the wake of a large-scale emergency may be counterproductive. Instead, the humanitarian community needs clearly defined information that can help in making critical decisions in mounting their programmes in order to save lives and restore livelihoods. By taking a close look at the data collected via Ushahidi in the wake of the Haiti earthquake, he concludes that crowdsourced data from affected communities may not be useful for supporting the response to a large-scale disaster.

: In this article, guest contributor Paul Currion looks at the potential for crowdsourcing data during large-scale humanitarian emergencies, as part of our "Deconstructing Mobile" series. Paul is an aid worker who has been working on the use of ICTs in large-scale emergencies for the last 10 years. He asks whether crowdsourcing adds significant value to responding to humanitarian emergencies, arguing that merely increasing the quantity of information in the wake of a large-scale emergency may be counterproductive. Instead, the humanitarian community needs clearly defined information that can help in making critical decisions in mounting their programmes in order to save lives and restore livelihoods. By taking a close look at the data collected via Ushahidi in the wake of the Haiti earthquake, he concludes that crowdsourced data from affected communities may not be useful for supporting the response to a large-scale disaster.

1. The Rise of Crowdsourcing in Emergencies

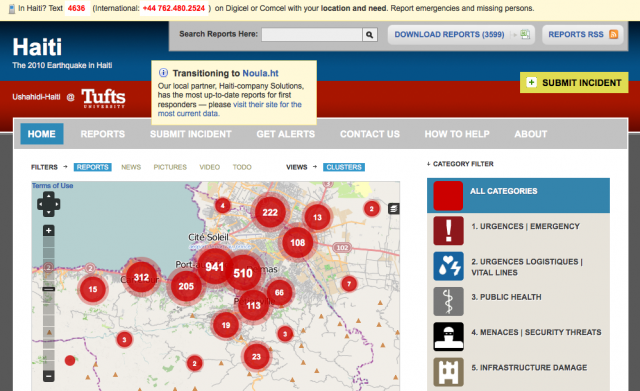

Ushahidi, the software platform for mapping incidents submitted by the crowd via SMS, email, Twitter or the web, has generated so many column inches of news coverage that the average person could be mistaken for thinking that it now plays a central role in coordinating crisis responses around the globe. At least this is what some articles say, such as Technology Review's profile of David Kobia, Director of Technology Development for Ushahidi. For most people, both inside and outside the sector, who lack the expertise to dig any deeper, column inches translate into credibility. If everybody's talking about Ushahidi, it must be doing a great job – right?

Maybe.

Ushahidi is the result of three important trends:

- Increased availability and utility of spatial data;

- Rapid growth of communication infrastructure, particularly mobile telephony; and

- Convergence of networks based on that infrastructure on Internet access.

Given those trends, projects like Ushahidi may be inevitable rather than unexpected, but inevitability doesn't give us any indication of how effective these projects are. Big claims are made about the way in which crowdsourcing is changing the way in which business is done in other sectors, and now attention has turned to the humanitarian sector. John Della Volpe's short article in the Huffington Post is an example of such claims:

"If a handful of social entrepreneurs from Kenya could create an open-source "social mapping" platform that successfully tracks and sheds light on violence in Kenya, earthquake response in Chile and Haiti, and the oil spill in the Gulf -- what else can we use it for?"

The key word in that sentence is “successfully”. There isn’t any evidence that Ushahidi “successfully” carried out these functions in these situations; only that an instance of the Ushahidi platform was set up. This is an extremely low bar to clear to achieve “success”, like claiming that a new business was successful because it had set up a website. There has lately been an unfounded belief that the transformative effects of the latest technology are positively inevitable and inevitably positive, simply by virtue of this technology’s existence.

2. What does Successful Crowdsourcing Look Like?

To be fair, it's hard to know what would constitute “success” for crowdsourcing in emergencies. In the case of Ushahidi, we could look at how many reports are posted on any given instance – but that record is disappointing, and the number of submissions for each Ushahidi instance is exceedingly small in comparison to the size of the affected population – including Haiti, where Ushahidi received the most public praise for its contribution.

In any case, the number of reports posted is not in itself a useful measure of impact, since those reports might consist of recycled UN situation reports and links to the Washington Post's “Your Earthquake Photos” feature. What we need to know is whether the service had a significant positive impact in helping communities affected by disaster. This is difficult to measure, even for experienced aid agencies whose work provides direct help. Perhaps the best we can do is ask a simple question: if the system worked exactly as promised, what added value would it deliver?

As Patrick Meier, a doctoral student and Director of Crisis Mapping and Strategic Partnerships for Ushahidi has explained, crowdsourcing would never be the only tool in the humanitarian information toolbox. That, of course, is correct and there is no doubt that crowdsourcing is useful for some activities – but is humanitarian response one of those activities?

A key question to ask is whether technology can improve information flow in humanitarian response. The answer is that it absolutely can, and that's exactly what many people, including this author, have been working on for the last 10 years. However, it is a fallacy to think that if the quantity of information increases, the quality of information increases as well. This is pretty obviously false, and, in fact, the reverse might be true.

From an aid worker’s perspective, our bandwidth is extremely limited, both literally and metaphorically. Those working in emergency response – official or unofficial, paid or unpaid, community-based or institution-based, governmental or non-governmental – don't need more information, they need better information. Specifically, they need clearly defined information which can help them to make critical decisions in mounting their programmes in order to save lives and restore livelihoods.

I wasn't involved with the Haiti response, which made me think that perhaps my doubts about Ushahidi were unfounded and that perhaps the data they had gathered could be useful. In the course of discussions on Patrick Meier's blog, I suggested that the best way for Ushahidi to show my position was wrong would be to present a use case to show how crowdsourced data could be used (as an example) by the Information Manager for the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Coordination Cluster, a position which I filled in Bangladesh and Georgia. Two months later, I decided to try that experiment for myself.

3. In Which I Look At The Data Most Carefully

The only crowdsourced data I have is the Ushahidi dataset for Haiti, but since Haiti is claimed as a success, that seemed like to be a good place to start. I started by downloading and reading through the dataset – the complete log of all reports posted in Ushahidi. It was a mix of two datastreams:

- Material published on the web or received via email, such as UN sitreps, media reports, and blog updates, and

- Messages sent in by the public via the 4636 SMS shortcode established during the emergency.

I was struck by two observations:

- One of the claims made by the Ushahidi team is that its work should be considered an additional datastream for a id workers. However, the first datastream is simply duplicating information that aid workers are already likely to receive.

- The 4636 messages were a novel datastream, but also the outcome of specific conditions which may not hold in places other than Haiti. The fact that there is a shortcode does not guarantee results, as can be seen in the virtually empty Pakistan Ushahidi deployment.

I considered that perhaps the 4636 messages could demonstrate some added value. They fell into three broad categories: the first was information about the developing situation, the second was people looking for information about family or friends missing after the earthquake, and the third and by far the largest, was general requests for help.

I tried to imagine that I had been handed this dataset on my deployment to Haiti. The first thing I would have to do is to read through it, clean it up, and transcribe it into a useful format rather than just a blank list. This itself would be a massive undertaking that can only be done by somebody on the ground who knows what a useful format would be. Unfortunately, speaking from personal experience, people on the ground simply don't have time for that, particularly if they are wrestling with other data such as NGO assessments or satellite images.

For the sake of argument, let's say that I somehow have the time to clean up the data. I now have a dataset of messages regarding the first three weeks of the response. 95% of those messages are for shelter, water and food. I could have told you that those would be the main needs even before I arrived in position, so that doesn't add any substantive value. On top of that, the data is up to 3 weeks old: I'd have to check each individual report just to find out just whether those people are still in the place that they were when they originally texted, and whether their needs have been met.

Again for the sake of argument, let's say that I have a sufficient number of staff (as opposed to zero, which is the number of staff you usually have when you're an information manager in the field) and they've checked every one of those requests. Now what? There are around 3000 individual “incidents” in the database, but most of those contain little to no detail about the people sending them. How many are included in the request, how many women, children and old people are there, what are their specific medical needs, exactly where they are located now – this is the vital information that aid agencies need to do their work, and it simply isn't there.

Once again for the sake of argument, let's say that all of those reports did contain that information – could I do something with it? If approximately 1.5 million people were affected by the disaster, those 3000 reports represent such a tiny fraction of the need that they can't realistically be used as a basis for programming response activities. One of the reasons we need aid agencies is economies of scale: procuring food for large populations is better done by taking the population as a whole. Individual cases, while important for the media, are almost useless as the basis for making response decisions after a large-scale disaster.

There is also this very basic technical question: once we have this crowdsourced data, what do we do with? In the case of Ushahidi, it was put on a Google Maps mash-up – but this is largely pointless for two reasons. First, there's a simple question of connectivity. Most aid workers and nearly all the population won't have reliable access to the Internet, and where they do, won't have time to browse through Google Maps. (It's worth noting that this problem is becoming less important as Internet connectivity, including the mobile web, improves globally – but also that the places and people prone to disasters tend to be the last to benefit from that connectivity.)

Second, from a functional perspective, the interface is rudimentary at best. The visual appeal of Ushahidi is similar to that of Powerpoint, casting an illusion of simplicity over what is, in fact, a complex situation. If I have 3000 text messages saying "I need food and water and shelter”, what added value is there from having those messages represented as a large circle on a map? The humanitarian community often lacks the capacity to analyse spatial data, but this map has almost no analytical capacity. The clustering of reports (where larger bubbles correspond to the places that most text messages refer to) may be a proxy for locations with the worst impact; but a pretty weak proxy derived from a self-selecting sample.

In the end, I was reduced to bouncing around the Ushahidi map, zooming in and out on individual reports – not something I would have time to do if I was actually in the field. Harsh as it sounds, my conclusion was that the data that crowdsourcing of this type is capable of collecting in a large-scale disaster response is operationally useless. The reason for this has nothing to do with Ushahidi, or the way that the system was implemented, but with the very nature of crowdsourcing itself.

4. Crowdsourcing Response or Digital Voluntourism?

One of the key definitions of “crowdsourcing” was provided by Jeff Howe in a Wired article that originally popularised the term: taking “a job traditionally performed by a designated agent (usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an undefined, generally large group of people in the form of an open call.” In the case of Haiti, part of the reason why people mistakenly thought crowdsourcing was successful, was because there were two different “crowds” being talked about.

The first was the global group of volunteers who came together to process the data that Ushahidi presented on its map. By all accounts, this was definitely a successful example of crowdsourcing as per Howe's definition. We can all agree that this group put a lot of effort into their work. However, the end result wasn’t especially useful. Furthermore, most of those volunteers won't show up for the next response – and in fact they didn't for Pakistan.

The media coverage of Ushahidi focuses mainly on this first crowd – the group of volunteers working remotely. Yet, the second crowd is much more important: the affected community. Reading through the Ushahidi data was heartbreaking, indeed. But we already knew that people needed food, water, shelter, medical aid – plus a lot more things that they wouldn't have been thinking of immediately as they stood in the ruins of their homes. In the Ushahidi model, this is the crowd that provides the actual data, the added value, but the question is whether crowdsourced data from affected communities could be useful from an operational perspective of organising the response to a large-scale disaster.

The data that this crowd can provide is unreliable for operational purposes for three reasons. First, you can't know how many people will contribute their information, a self-selection bias that will skew an operational response. Second, the information that they do provide must be checked – not because affected populations may be lying, but because people in the immediate aftermath of a large-scale disaster do not necessarily know all that they specifically need or may not provide complete information. Third, the data is by nature extremely transitory, out-of-date as soon as it's posted on the map.

Taken together, these three mean that aid agencies are going to have to carry out exactly the same needs assessments that they would have anyway – in which case, what use was that information in the first place?

5. Is Crowdsourcing Raising Expectations That Cannot be Met?

Many of the critiques that the crowdsourcing crowd defend against are questions about how to verify the accuracy of crowdsourced information, but I don't think that's the real problem. It's the nature of an emergency that all information is provisional. The real question is whether it's useful.

So to some extent those questions are a distraction from the real problems: how to engage with affected communities to help them respond to emergencies more effectively, and how to coordinate aid agencies to ensure and effective response. On the face of it, crowdsourcing looks like it can help to address those problems. In fact, the opposite may be true.

Disaster response on the scale of the Haiti earthquake or the Pakistan floods is not simply a question of aggregating individual experiences. Anecdotes about children being pulled from rubble by Search and Rescue teams are heart-warming and may help raise money for aid agencies but such stories are relatively incidental when the humanitarian need is clean water for 1 million people living in that rubble. Crowdsourced information – that is, information voluntarily submitted in an open call to the public – will not ever provide the sort of detail that aid agencies need to procure and supply essential services to entire populations.

That doesn't mean that crowdsourcing is useless: based on the evidence from Haiti, Ushahidi did contribute to Search and Rescue (SAR). The reason for that is because SAR requires the receipt of a specific request for a specific service at a specific location to be delivered by a specific provider – the opposite of crowdsourcing. SAR is far from being a core component of most humanitarian responses, and benefits from a chain of command that makes responding much simpler. Since that same chain of command does not exist in the wider humanitarian community, ensuring any response to an individual 4636 message is almost impossible.

This in turn raises questions of accountability – is it wholly responsible to set up a shortcode system if there is no response capability behind it, or are we just raising the expectations of desperate people?

6. Could Crowdsourcing Add Value to Humanitarian Efforts?

Perhaps it could. However, the problem is that nobody who is promoting crowdsourcing currently has presented convincing arguments for that added value. To the extent that it's a crowdsourcing tool, Ushahidi is not useful; to the extent that it's useful, Ushahidi is not a crowdsourcing tool.

To their credit, this hasn't gone unnoticed by at least some of the Ushahidi team, and there seems to be something of a retreat from crowdsourcing, described in this post by one of the developers, Chris Blow:

One way to solve this: forget about crowdsourcing. Unless you want to do a huge outreach campaign, design your system to be used by just a few people. Start with the assumption that you are not going to get a single report from anyone who is not on your payroll. You can do a lot with just a few dedicated reporters who are pushing reports into the system, curating and aggregating sources."

At least one of the Ushahidi team members now talks about “bounded crowdsourcing” which is a nonsensical concept. By definition, if you select the group doing the reporting, they're not a crowd in the sense that Howe explained in his article. This may be an area where Ushahidi would be useful, since a selected (and presumably trained) group of reporters could deliver the sort of structured data with more consistent coverage that is actually useful – the opposite of what we saw in Haiti. Such an approach, however, is not crowdsourcing.

Crowdsourcing can be useful on the supply side: for example, one of the things that the humanitarian community does need is increased capacity to process data. One of the success stories in Haiti was the work of the OpenStreetMap (OSM) project, where spatial data derived from existing maps and satellite images was processed remotely to build up a far better digital map of Haiti than existed previously. However, this processing was carried out by the already existing OSM community rather than by the large and undefined crowd that Jeff Howe described.

Nevertheless this is something that the humanitarian community should explore, especially for data that has a long-term benefit for affected countries (such as core spatial data). To have available a recognised group of data processors who can do the legwork that is essential but time-consuming would be a real asset to the community – but there we've moved away from the crowd again.

7. A Small Conclusion

My critique of crowdsourcing – shared by other people working at the interface of humanitarian response and technology – is not that it is disruptive to business as usual. My critique is that it doesn't work – not just that it doesn't work given the constraints of the operational environment (which Ushahidi's limited impact in past deployments shows to be largely true), but that even if the concept worked perfectly, it still wouldn't offer sufficient value to warrant investing in.

Unfortunately, because Ushahidi rests its case almost entirely on the crowdsourcing concept, this article may be interpreted as an attack on Ushahidi and the people working on it. However, all of the questions I've raised here are not directed solely at Ushahidi (although I hope that there will be more debate about some of the points raised) but hopefully will become part of a wider and more informed debate about social media in general within the humanitarian community.

Resources are always scarce in the humanitarian sector, and the question of which technology to invest in is a critical one. We need more informed voices discussing these issues, based on concrete use cases because that's the only way we can test the claims that are made about technology. For while the tools that we now have at our disposal are important, we have a responsibility to use them for the right tasks.

Image credit: Urban Search and Rescue Team, with assistance from U.S. military personnel, coordinate plans before a search and rescue mission in order to find survivors in Port-au-Prince. U.S. Navy Photo.

| “If all You Have is a Hammer” - How Useful is Humanitarian Crowdsourcing? data sheet 21330 Views | |

|---|---|

| Countries: | Haiti |

Thanks for the link

Anahi:

Thanks for commenting, it's good to have somebody who's actually involved with Ushahidi in this discussion. I read that Irin article when it was published - it's exactly the sort of uncritical writing that I talk about at the start of the article. Can you help me to understand exactly how Pakreport helps affected communities and aid organisations?

The burden of success

Senam:

I am saying that your criticism of Ushahidi must be viewed as a cheap and too common assault on African initiatives when it comes to so-called "development work".

I'm a little puzzled why it must be viewed that way when the article isn't about development work and doesn't mention Africa at all.

I am saying that I could deconstruct your whole existence, your "raison d'etre" as "aid/humanitarian worker", why and how you became who you are, "an expert in humanitarian crisis". We won't go there.

I'm very interested to read your deconstruction of my existence, so please go ahead.

I can say that you are wrong to assume that Ushahidi rests its case entirely on the crowsourcing concept.

What I said was that Ushahidi rests its case almost entirely on the crowdsourcing concept, which it does. On their website, Ushahidi is described as “a platform that was originally built to crowdsource crisis information”, SwiftRiver is described as “software that uses algorithms and crowdsourcing to validate and filter news”, and Crowdmap is billed as “instant crowdsourcing.”

In case that's not enough, here's Patrick Meier at PopTech (http://vimeo.com/11842618), where he explains exactly how the creation of Ushahidi was based on crowdsourcing, saying “what Ushahidi does is take this crowdsourcing approach and enable people to tell their own stories.” So yes, Ushahidi rests it case almost entirely on the crowdsourcing concept.

Why do you put the burden of success on the creators of the tool? Is that really their responsibility?

No, the burden of success is on the users of the tool. The burden on the creators of the tool is to engage in open discussion about the potential and limitations, and to be honest about what it is actually capable of in order to avoid raising users' expectations about what it can do.

Yes they have [done an excellent job]. They innovated by creating a new tool with the potential of doing many things...including crowsourcing in a disaster.

We can only judge whether they have done an excellent job based on the performance of that tool. The point of this article is that so far that tool has not performed well, and that I find it difficult to see how it can perform well, in the sense of having a significant positive impact on the lives of people affected by disaster. If you can explain to me how it might have such an impact, then please go ahead: this is what I've asked the Ushahidi team for, but have so far received no response.

Not African

Senam: If Ushahidi had actually been created out of Africa, that would have been great. The majority of the staff lives in the US and it is headed by Erik Hersman, who while now is living in Nairobi, is most assuredly not African. And the money for it has all come from US & EU NGO's, not Africa, so Ushahidi, despite the name is not an African product.

Not really dealing with...

Paul:

I am not implying that you are a racist. Only you know the answer to that question. I am saying that your criticism of Ushahidi must be viewed as a cheap and too common assault on African initiatives when it comes to so-called "development work". It is very easy to deconstruct but a bit more difficult to innovate. I am saying that I could deconstruct your whole existence, your "raison d'etre" as "aid/humanitarian worker", why and how you became who you are, "an expert in humanitarian crisis". We won't go there.

You responded :"This article is entirely about the merits of Ushahidi, and has nothing to say about the people behind it or where it came from." but you wrote: "Unfortunately, because Ushahidi rests its case almost entirely on the crowdsourcing concept, this article may be interpreted as an attack on Ushahidi and the people working on it."

So you do agree that it could be interpreted as an attack on the people working on it. I don't speak for them, don't even know them, I can say that you are wrong to assume that Ushahidi rests its case entirely on the crowsourcing concept. Can you maybe give it a bit more time, and account for the emergence of additional technology? Creative use? Hybrid use? Why do you put the burden of success on the creators of the tool? Is that really their responsibility?

You responded: "I agree that development aid has been a failure, but this article is not about development aid. It's about humanitarian aid, the life-saving assistance required when local systems collapse under the weight of a massive external shock." I am glad you think that humanitarian aid has been a success. People in the DRC or Haiti will beg to differ but that's a another story.

They have done an excellent job. Yes they have. They innovated by creating a new tool with the potential of doing many things...including crowsourcing in a disaster. As to how it is used, why don't we all work on it so next time I can write that Paul Currion did an outstanding job by using Ushahidi in a creative way to respond to the devastating floods currently affecting the people of Benin?

Crowdsouring for Citizen Reporting in Elections

For those of you interested in the use of crowdsourcing in elections / citizen reporting during elections, you may be interested in this article on "Cutting Through the Hype: Why Citizen Reporting is not Election Monitoring."

Surely you jest! Oh.

In fact, the Jester believes much of Ushahidi's positive value to date has been in raising public consciousness about certain global events.

It's interesting that you say that, because that's where I think Ushahidi's real value lies. It's in awareness-raising and advocacy, much like the Crisis in Darfur project was (http://earth.google.com/outreach/cs_darfur.html), and this is a good and powerful thing.

Yet that's a very different thing to claiming that you are revolutionising the humanitarian world, or that your project was directly responsible for saving lives. I realise that a lot of people are heavily invested in this version of events, but that isn't good enough for me.

Paul Currion's key insight, though, is that for aid purposes, even (1) and (2) only go so far, because (3) is missing. And, what's (3)? (3) is human/institutional intent and capacity on the ground. As wonderful as Ushahidi (1)+(2) is, it makes no difference if there isn't (3), a force on the ground that can actually respond meaningfully to the noisy information (1)+(2) produces.

I agree with this only partly. My concern is not merely that there wasn't a response capacity in place, it's that the sort of information that crowdsourcing provides can't be very useful for the sort of response capacity that we have, or are likely to have in the future, in this kind of disaster.

Mixing crises?

Juergen:

However, since I've seen where Ushahidi came from and that the initial motivation was to keep a record of the many incidents in Kenya during the post election violence in 2008, Ushahidi to me is just a tool - and I don't expect to divide by zero with it. Instead, I am happy that a negative event like the post election violence in Kenya eventually triggered the start of a positive development.

It may be hard to believe, but I am extremely happy about the positive momentum that Ushahidi has gathered, and I wish the iHub the best of luck. If this is the start of something big for the African (initially Kenyan, I guess) technology sector, that would be fantastic – but that's not the criteria for judging whether crowdsourcing works in this context.

You raise an important point which I didn't make in the original article. Ushahidi was developed to track election violence, and that's a type of crisis; but a colossal earthquake in Haiti is a completely different type of crisis. I think it's this conflation of different types of crisis that may have lead us in the wrong direction – surely one tool is unlikely to be suitable for both?

Hence the title of this piece, which comes from Abraham Maslow: “if all you have is a hammer, every problem looks like a nail.”

As for the attention and media hype they've received: is that bad? Is it about the money?

It's about the resources: not really money, but organisational time. Given that those resources are (severely) constrained, it's definitely an appropriate question to ask.

You also mentioned the watsan test @ humanitarianreform. Is that something similar to the recently launched FLOW mapping by Water4People? Or is yours focused on crisis/emergency issues?

This article, my work and the clusters are focused solely on humanitarian response, although obviously the line between that and recovery/development often gets blurred. Thanks for the link to Flow mapping, it looks very interesting.

This - having the gathered data and actually using it for tangible decisions - imo still is the biggest issue that a tool like Ushahidi never attempted to solve. I never expected it to do that, though.

I'm very interested now: what do you expect that type of tool to do?

Dealing with it...

Senam:

While I admire your passion, in future you might want to refrain from implying that I'm a racist. It doesn't really help your argument.

This is less about the merits of Ushahidi and more about the people behind it and where it came from.

No, it isn't. This article is entirely about the merits of Ushahidi, and has nothing to say about the people behind it or where it came from.

The concept of Aid … serves a purpose for donor countries, employs aid workers, contractors and make people feel good. But helping the poor? If I applied Paul’s logic, it has been a monstrous failure.

I agree that development aid has been a failure, but this article is not about development aid. It's about humanitarian aid, the life-saving assistance required when local systems collapse under the weight of a massive external shock.

They have done an excellent job

This is the point of the article: what evidence do you have that they've done an excellent job?

Let's not focus solely on Ushahidi

Andrew:

All of this has been needed to be said for a very long time in regards to Ushahidi. They are playing with peoples' lives and this isn't something to be taken lightly.

I know that this article focuses on Ushahidi, but I do want to emphasise that these questions need to be asked about all social media – in fact, the basic question needs to be asked about any new technology. I do think there are particular issues with how crowdsourcing projects might be raising expectations in a way that could create many problems.

PakReport

http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/JALR-89QCYT?OpenDocument

Enjoy!

Post new comment