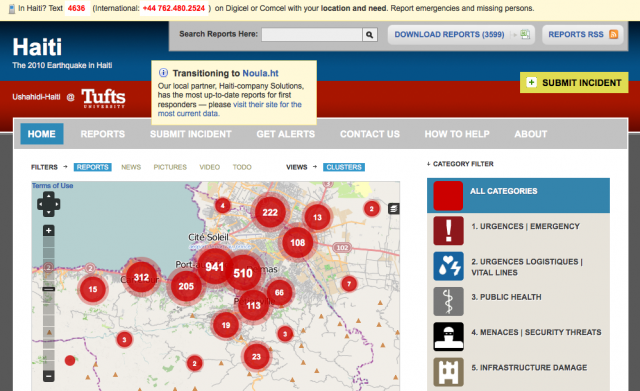

Editor’s Note : In this article, guest contributor Paul Currion looks at the potential for crowdsourcing data during large-scale humanitarian emergencies, as part of our "Deconstructing Mobile" series. Paul is an aid worker who has been working on the use of ICTs in large-scale emergencies for the last 10 years. He asks whether crowdsourcing adds significant value to responding to humanitarian emergencies, arguing that merely increasing the quantity of information in the wake of a large-scale emergency may be counterproductive. Instead, the humanitarian community needs clearly defined information that can help in making critical decisions in mounting their programmes in order to save lives and restore livelihoods. By taking a close look at the data collected via Ushahidi in the wake of the Haiti earthquake, he concludes that crowdsourced data from affected communities may not be useful for supporting the response to a large-scale disaster.

: In this article, guest contributor Paul Currion looks at the potential for crowdsourcing data during large-scale humanitarian emergencies, as part of our "Deconstructing Mobile" series. Paul is an aid worker who has been working on the use of ICTs in large-scale emergencies for the last 10 years. He asks whether crowdsourcing adds significant value to responding to humanitarian emergencies, arguing that merely increasing the quantity of information in the wake of a large-scale emergency may be counterproductive. Instead, the humanitarian community needs clearly defined information that can help in making critical decisions in mounting their programmes in order to save lives and restore livelihoods. By taking a close look at the data collected via Ushahidi in the wake of the Haiti earthquake, he concludes that crowdsourced data from affected communities may not be useful for supporting the response to a large-scale disaster.

1. The Rise of Crowdsourcing in Emergencies

Ushahidi, the software platform for mapping incidents submitted by the crowd via SMS, email, Twitter or the web, has generated so many column inches of news coverage that the average person could be mistaken for thinking that it now plays a central role in coordinating crisis responses around the globe. At least this is what some articles say, such as Technology Review's profile of David Kobia, Director of Technology Development for Ushahidi. For most people, both inside and outside the sector, who lack the expertise to dig any deeper, column inches translate into credibility. If everybody's talking about Ushahidi, it must be doing a great job – right?

Maybe.

Ushahidi is the result of three important trends:

- Increased availability and utility of spatial data;

- Rapid growth of communication infrastructure, particularly mobile telephony; and

- Convergence of networks based on that infrastructure on Internet access.

Given those trends, projects like Ushahidi may be inevitable rather than unexpected, but inevitability doesn't give us any indication of how effective these projects are. Big claims are made about the way in which crowdsourcing is changing the way in which business is done in other sectors, and now attention has turned to the humanitarian sector. John Della Volpe's short article in the Huffington Post is an example of such claims:

"If a handful of social entrepreneurs from Kenya could create an open-source "social mapping" platform that successfully tracks and sheds light on violence in Kenya, earthquake response in Chile and Haiti, and the oil spill in the Gulf -- what else can we use it for?"

The key word in that sentence is “successfully”. There isn’t any evidence that Ushahidi “successfully” carried out these functions in these situations; only that an instance of the Ushahidi platform was set up. This is an extremely low bar to clear to achieve “success”, like claiming that a new business was successful because it had set up a website. There has lately been an unfounded belief that the transformative effects of the latest technology are positively inevitable and inevitably positive, simply by virtue of this technology’s existence.

2. What does Successful Crowdsourcing Look Like?

To be fair, it's hard to know what would constitute “success” for crowdsourcing in emergencies. In the case of Ushahidi, we could look at how many reports are posted on any given instance – but that record is disappointing, and the number of submissions for each Ushahidi instance is exceedingly small in comparison to the size of the affected population – including Haiti, where Ushahidi received the most public praise for its contribution.

In any case, the number of reports posted is not in itself a useful measure of impact, since those reports might consist of recycled UN situation reports and links to the Washington Post's “Your Earthquake Photos” feature. What we need to know is whether the service had a significant positive impact in helping communities affected by disaster. This is difficult to measure, even for experienced aid agencies whose work provides direct help. Perhaps the best we can do is ask a simple question: if the system worked exactly as promised, what added value would it deliver?

As Patrick Meier, a doctoral student and Director of Crisis Mapping and Strategic Partnerships for Ushahidi has explained, crowdsourcing would never be the only tool in the humanitarian information toolbox. That, of course, is correct and there is no doubt that crowdsourcing is useful for some activities – but is humanitarian response one of those activities?

A key question to ask is whether technology can improve information flow in humanitarian response. The answer is that it absolutely can, and that's exactly what many people, including this author, have been working on for the last 10 years. However, it is a fallacy to think that if the quantity of information increases, the quality of information increases as well. This is pretty obviously false, and, in fact, the reverse might be true.

From an aid worker’s perspective, our bandwidth is extremely limited, both literally and metaphorically. Those working in emergency response – official or unofficial, paid or unpaid, community-based or institution-based, governmental or non-governmental – don't need more information, they need better information. Specifically, they need clearly defined information which can help them to make critical decisions in mounting their programmes in order to save lives and restore livelihoods.

I wasn't involved with the Haiti response, which made me think that perhaps my doubts about Ushahidi were unfounded and that perhaps the data they had gathered could be useful. In the course of discussions on Patrick Meier's blog, I suggested that the best way for Ushahidi to show my position was wrong would be to present a use case to show how crowdsourced data could be used (as an example) by the Information Manager for the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Coordination Cluster, a position which I filled in Bangladesh and Georgia. Two months later, I decided to try that experiment for myself.

3. In Which I Look At The Data Most Carefully

The only crowdsourced data I have is the Ushahidi dataset for Haiti, but since Haiti is claimed as a success, that seemed like to be a good place to start. I started by downloading and reading through the dataset – the complete log of all reports posted in Ushahidi. It was a mix of two datastreams:

- Material published on the web or received via email, such as UN sitreps, media reports, and blog updates, and

- Messages sent in by the public via the 4636 SMS shortcode established during the emergency.

I was struck by two observations:

- One of the claims made by the Ushahidi team is that its work should be considered an additional datastream for a id workers. However, the first datastream is simply duplicating information that aid workers are already likely to receive.

- The 4636 messages were a novel datastream, but also the outcome of specific conditions which may not hold in places other than Haiti. The fact that there is a shortcode does not guarantee results, as can be seen in the virtually empty Pakistan Ushahidi deployment.

I considered that perhaps the 4636 messages could demonstrate some added value. They fell into three broad categories: the first was information about the developing situation, the second was people looking for information about family or friends missing after the earthquake, and the third and by far the largest, was general requests for help.

I tried to imagine that I had been handed this dataset on my deployment to Haiti. The first thing I would have to do is to read through it, clean it up, and transcribe it into a useful format rather than just a blank list. This itself would be a massive undertaking that can only be done by somebody on the ground who knows what a useful format would be. Unfortunately, speaking from personal experience, people on the ground simply don't have time for that, particularly if they are wrestling with other data such as NGO assessments or satellite images.

For the sake of argument, let's say that I somehow have the time to clean up the data. I now have a dataset of messages regarding the first three weeks of the response. 95% of those messages are for shelter, water and food. I could have told you that those would be the main needs even before I arrived in position, so that doesn't add any substantive value. On top of that, the data is up to 3 weeks old: I'd have to check each individual report just to find out just whether those people are still in the place that they were when they originally texted, and whether their needs have been met.

Again for the sake of argument, let's say that I have a sufficient number of staff (as opposed to zero, which is the number of staff you usually have when you're an information manager in the field) and they've checked every one of those requests. Now what? There are around 3000 individual “incidents” in the database, but most of those contain little to no detail about the people sending them. How many are included in the request, how many women, children and old people are there, what are their specific medical needs, exactly where they are located now – this is the vital information that aid agencies need to do their work, and it simply isn't there.

Once again for the sake of argument, let's say that all of those reports did contain that information – could I do something with it? If approximately 1.5 million people were affected by the disaster, those 3000 reports represent such a tiny fraction of the need that they can't realistically be used as a basis for programming response activities. One of the reasons we need aid agencies is economies of scale: procuring food for large populations is better done by taking the population as a whole. Individual cases, while important for the media, are almost useless as the basis for making response decisions after a large-scale disaster.

There is also this very basic technical question: once we have this crowdsourced data, what do we do with? In the case of Ushahidi, it was put on a Google Maps mash-up – but this is largely pointless for two reasons. First, there's a simple question of connectivity. Most aid workers and nearly all the population won't have reliable access to the Internet, and where they do, won't have time to browse through Google Maps. (It's worth noting that this problem is becoming less important as Internet connectivity, including the mobile web, improves globally – but also that the places and people prone to disasters tend to be the last to benefit from that connectivity.)

Second, from a functional perspective, the interface is rudimentary at best. The visual appeal of Ushahidi is similar to that of Powerpoint, casting an illusion of simplicity over what is, in fact, a complex situation. If I have 3000 text messages saying "I need food and water and shelter”, what added value is there from having those messages represented as a large circle on a map? The humanitarian community often lacks the capacity to analyse spatial data, but this map has almost no analytical capacity. The clustering of reports (where larger bubbles correspond to the places that most text messages refer to) may be a proxy for locations with the worst impact; but a pretty weak proxy derived from a self-selecting sample.

In the end, I was reduced to bouncing around the Ushahidi map, zooming in and out on individual reports – not something I would have time to do if I was actually in the field. Harsh as it sounds, my conclusion was that the data that crowdsourcing of this type is capable of collecting in a large-scale disaster response is operationally useless. The reason for this has nothing to do with Ushahidi, or the way that the system was implemented, but with the very nature of crowdsourcing itself.

4. Crowdsourcing Response or Digital Voluntourism?

One of the key definitions of “crowdsourcing” was provided by Jeff Howe in a Wired article that originally popularised the term: taking “a job traditionally performed by a designated agent (usually an employee) and outsourcing it to an undefined, generally large group of people in the form of an open call.” In the case of Haiti, part of the reason why people mistakenly thought crowdsourcing was successful, was because there were two different “crowds” being talked about.

The first was the global group of volunteers who came together to process the data that Ushahidi presented on its map. By all accounts, this was definitely a successful example of crowdsourcing as per Howe's definition. We can all agree that this group put a lot of effort into their work. However, the end result wasn’t especially useful. Furthermore, most of those volunteers won't show up for the next response – and in fact they didn't for Pakistan.

The media coverage of Ushahidi focuses mainly on this first crowd – the group of volunteers working remotely. Yet, the second crowd is much more important: the affected community. Reading through the Ushahidi data was heartbreaking, indeed. But we already knew that people needed food, water, shelter, medical aid – plus a lot more things that they wouldn't have been thinking of immediately as they stood in the ruins of their homes. In the Ushahidi model, this is the crowd that provides the actual data, the added value, but the question is whether crowdsourced data from affected communities could be useful from an operational perspective of organising the response to a large-scale disaster.

The data that this crowd can provide is unreliable for operational purposes for three reasons. First, you can't know how many people will contribute their information, a self-selection bias that will skew an operational response. Second, the information that they do provide must be checked – not because affected populations may be lying, but because people in the immediate aftermath of a large-scale disaster do not necessarily know all that they specifically need or may not provide complete information. Third, the data is by nature extremely transitory, out-of-date as soon as it's posted on the map.

Taken together, these three mean that aid agencies are going to have to carry out exactly the same needs assessments that they would have anyway – in which case, what use was that information in the first place?

5. Is Crowdsourcing Raising Expectations That Cannot be Met?

Many of the critiques that the crowdsourcing crowd defend against are questions about how to verify the accuracy of crowdsourced information, but I don't think that's the real problem. It's the nature of an emergency that all information is provisional. The real question is whether it's useful.

So to some extent those questions are a distraction from the real problems: how to engage with affected communities to help them respond to emergencies more effectively, and how to coordinate aid agencies to ensure and effective response. On the face of it, crowdsourcing looks like it can help to address those problems. In fact, the opposite may be true.

Disaster response on the scale of the Haiti earthquake or the Pakistan floods is not simply a question of aggregating individual experiences. Anecdotes about children being pulled from rubble by Search and Rescue teams are heart-warming and may help raise money for aid agencies but such stories are relatively incidental when the humanitarian need is clean water for 1 million people living in that rubble. Crowdsourced information – that is, information voluntarily submitted in an open call to the public – will not ever provide the sort of detail that aid agencies need to procure and supply essential services to entire populations.

That doesn't mean that crowdsourcing is useless: based on the evidence from Haiti, Ushahidi did contribute to Search and Rescue (SAR). The reason for that is because SAR requires the receipt of a specific request for a specific service at a specific location to be delivered by a specific provider – the opposite of crowdsourcing. SAR is far from being a core component of most humanitarian responses, and benefits from a chain of command that makes responding much simpler. Since that same chain of command does not exist in the wider humanitarian community, ensuring any response to an individual 4636 message is almost impossible.

This in turn raises questions of accountability – is it wholly responsible to set up a shortcode system if there is no response capability behind it, or are we just raising the expectations of desperate people?

6. Could Crowdsourcing Add Value to Humanitarian Efforts?

Perhaps it could. However, the problem is that nobody who is promoting crowdsourcing currently has presented convincing arguments for that added value. To the extent that it's a crowdsourcing tool, Ushahidi is not useful; to the extent that it's useful, Ushahidi is not a crowdsourcing tool.

To their credit, this hasn't gone unnoticed by at least some of the Ushahidi team, and there seems to be something of a retreat from crowdsourcing, described in this post by one of the developers, Chris Blow:

One way to solve this: forget about crowdsourcing. Unless you want to do a huge outreach campaign, design your system to be used by just a few people. Start with the assumption that you are not going to get a single report from anyone who is not on your payroll. You can do a lot with just a few dedicated reporters who are pushing reports into the system, curating and aggregating sources."

At least one of the Ushahidi team members now talks about “bounded crowdsourcing” which is a nonsensical concept. By definition, if you select the group doing the reporting, they're not a crowd in the sense that Howe explained in his article. This may be an area where Ushahidi would be useful, since a selected (and presumably trained) group of reporters could deliver the sort of structured data with more consistent coverage that is actually useful – the opposite of what we saw in Haiti. Such an approach, however, is not crowdsourcing.

Crowdsourcing can be useful on the supply side: for example, one of the things that the humanitarian community does need is increased capacity to process data. One of the success stories in Haiti was the work of the OpenStreetMap (OSM) project, where spatial data derived from existing maps and satellite images was processed remotely to build up a far better digital map of Haiti than existed previously. However, this processing was carried out by the already existing OSM community rather than by the large and undefined crowd that Jeff Howe described.

Nevertheless this is something that the humanitarian community should explore, especially for data that has a long-term benefit for affected countries (such as core spatial data). To have available a recognised group of data processors who can do the legwork that is essential but time-consuming would be a real asset to the community – but there we've moved away from the crowd again.

7. A Small Conclusion

My critique of crowdsourcing – shared by other people working at the interface of humanitarian response and technology – is not that it is disruptive to business as usual. My critique is that it doesn't work – not just that it doesn't work given the constraints of the operational environment (which Ushahidi's limited impact in past deployments shows to be largely true), but that even if the concept worked perfectly, it still wouldn't offer sufficient value to warrant investing in.

Unfortunately, because Ushahidi rests its case almost entirely on the crowdsourcing concept, this article may be interpreted as an attack on Ushahidi and the people working on it. However, all of the questions I've raised here are not directed solely at Ushahidi (although I hope that there will be more debate about some of the points raised) but hopefully will become part of a wider and more informed debate about social media in general within the humanitarian community.

Resources are always scarce in the humanitarian sector, and the question of which technology to invest in is a critical one. We need more informed voices discussing these issues, based on concrete use cases because that's the only way we can test the claims that are made about technology. For while the tools that we now have at our disposal are important, we have a responsibility to use them for the right tasks.

Image credit: Urban Search and Rescue Team, with assistance from U.S. military personnel, coordinate plans before a search and rescue mission in order to find survivors in Port-au-Prince. U.S. Navy Photo.

| “If all You Have is a Hammer” - How Useful is Humanitarian Crowdsourcing? data sheet 21332 Views | |

|---|---|

| Countries: | Haiti |

Out of Africa...Deal with it!

I am coming a bit late to this debate but I am happy to see that many thoughtful people already made the point that this unnecessarily harsh criticism (definitely not a critique) is premature. This is less about the merits of Ushahidi and more about the people behind it and where it came from... Whenever African intellectuals wander off the reservation onto the “chasse gardée” of “aid workers” they are pilloried. How dare they use common sense as a start-up idea to bring a potentially disruptive product into the mix? They are supposed to be consumers of ideas and add-on collaborators.

There are so many assumptions in this piece that I don’t even know where to start. “Paul is an aid worker who has been working on the use of ICTs in large-scale emergencies for the last 10 years” says the introduction of the author. So those are his credentials? What does it mean? Aid worker? Maybe we need to start by deconstructing that first. The concept of Aid has its critics (me included) and a D- (my students know I am a generous grader) hasn’t stopped it. Why? Because it serves a purpose for donor countries, employs aid workers, contractors and make people feel good. But helping the poor? If I applied Paul’s logic, it has been a monstrous failure. Africa is poorer today than it was 50 years ago when most countries became independent and “international development” was introduced to it. So let's not deconstruct Ushahidi in a vacuum. Paul ought to ask himself some existential questions first.

Ushahidi is a tool. Like the mobile phone, the internet; it is up to all of us to think critically about how we can add value to it and use it in ways that even its founders never dreamed of. They have done an excellent job…Sorry if they did it from Africa. Deal with it!

We can't live without volunteers, but...

Andrew:

Another issue is not considering the array of volunteers. The crowd does not mean amateur.

I'm not opposed to the use of volunteers; I do not think volunteers are necessarily amateurs; and the NGO community is based on a long and rich volunteer history (which I am part of). While this may be a new type of volunteer endeavour, it's subject to exactly the same constraints and provides many of the same opportunities as any type of volunteer endeavour. However I don't see any acknowledgement of that in the discussion – while in theory volunteers are an infinite resource, in practice they are not.

I agree that there are concerns, and misinformed reporting on effectiveness in many tools. However, I believe also that the perspective has been too narrow in defining a large capability in volunteer crisis response information assistance through the perspective of a single tool or set of deployments.

I agree with you. In 2005 I wrote an essay about how we were seeing a blossoming of interesting technology projects post-Katrina (still available at http://www.humanitarian.info/ict-and-katrina/). Anybody reading that essay will see immediately that I am not opposed to these developments in social media – in fact, that's exactly what I was hoping for.

However we have to draw our conclusions based on the evidence available, right? Misinformed reporting plays a role in my frustration, but nobody seems to be interested in correcting that misinformation – and when people persist in claiming that their tool will revolutionise the sector based on no evidence, that's when I get suspicious.

The mechanics of the revolution

Mark: I wrote a long response that tried to address each of your (very relevant) points, but in the end I realised that our disagreement hinges around this statement:

It seems like a little early to be so definitive about the value of crowdsourcing. Let's see where we are in even 12 months.

I'm not being definitive about the value of crowdsourcing. I'm offering an opinion, and I'm hoping that people will push back exactly as you're doing. My frustration I have about these discussions – and I say this with all due respect – is that none of the defences of crowdsourcing for humanitarian operations seem to have any grounding in reality.

Instead what we get – and I'm afraid I have to include your response in this, Mark – are grandiose yet vague promises that crowdsourcing will not just deliver added value, but revolutionise humanitarian response. All I'm saying is that I need more than those vague promises, and here's why. Imagine that I came to you and said:

“I've got a revolutionary new approach to community sanitation which your organisation must adopt or be left behind. It's been set up several times before, although almost nobody used it and there's no evidence that it had any impact. This approach will definitely save lives, although we can't explain exactly how, or how many lives, or what it will cost, or when it will finally work.”

I don't think that you would give such a proposition the time of day if it was in sanitation, Mark – so why are you prepared to accept it in the case of ICT? At some point somebody has to stand up and say: is this actually going anywhere? So all I'm looking for is a compelling use case scenario taking account of the way large-scale humanitarian response actually work.

What's the business case?

Carrie:

I understand that you don't "see what use it would be to – specifically – somebody actually coordinating the delivery of humanitarian aid", but perhaps, just maybe, it will turn out to be something far more important or useful than any of us can currently imagine?

I absolutely don't dismiss the concept of crowdsourcing, which is why I'm hoping that those who make claims about the impact of crowdsourcing will provide me with counter-examples, to show that I'm wrong.

This article was written partly out of frustration that so far all we have is grandiose rhetoric about how crowdsourcing will revolutionise humanitarian response – but nobody actually seems to be able to explain exactly how it will do that.

You may well be right – crowdsourcing (and other approaches made possible through social media) may turn out to be far more important than I can imagine. However that's not a business case, and that's what we need to have in front of us.

a bit off-topic, but..

R: Ushahidi has opened several important dialogues - one about technology for humanitarian purposes, one about the utility of crowdsourcing vs. command-and-control, centralized information systems, and one about the potential of African IT entrepreneurship...

P: I'm not sure I agree with you. The dialogue about the potential of African IT entrepreneurship – possibly, but what is that dialogue, exactly?..

Without Ushahidi we wouldn't have the iHub in Kenya, so the "millions that Ushahidi received" (@Adam) are obviously put to good use.

As a Kenyan-German blogger, I've followed the development of Ushahidi right from the very start and also beta tested Crowdmap earlier this year. There were of course a lot of moments when I asked myself & the Ushahidi team what they will do with all that data. However, since I've seen where Ushahidi came from and that the initial motivation was to keep a record of the many incidents in Kenya during the post election violence in 2008, Ushahidi to me is just a tool - and I don't expect to divide by zero with it. Instead, I am happy that a negative event like the post election violence in Kenya eventually triggered the start of a positive development.

As for the attention and media hype they've received: is that bad? Is it about the money?

Paul, I understand your questions and diligent approach to analyzing the gathered data. Frankly said, I also never expected much to result from that data, whether crowdsourced or prepared by a team of volunteers. This, however, as you also mentioned, isn't a typical Ushahidi problem, but the nature of such data, I think.

"How useful is Humanitarian Crowdsourcing?" - I think it's quite useful, but not necessarily in an emergency situation. I understand that Haiti was an unexpected test for the tool, so things may be a bit different by now.

You also mentioned the watsan test @ humanitarianreform. Is that something similar to the recently launched FLOW mapping by Water4People? Or is yours focused on crisis/emergency issues?

You know I've also thought about using Ushahidi/Crowdmap for a revised edition of sanimap.net (@ .com) and to see if it will be the right tool for mapping toilets. Am still testing but I like the idea that I won't have to reinvent the wheel while using Ushahidi, so this may be one of the reaons for the success and hype of it. Else - mapping a toilet on a world map somewhere on the internet surely doesn't have any impact at all (except for the political scientists who would use it for their project indicators).

This - having the gathered data and actually using it for tangible decisions - imo still is the biggest issue that a tool like Ushahidi never attempted to solve. I never expected it to do that, though.

- @jke

Technology amplifies institutional intent and capacity

Terrific article on Ushahidi! A nice articulation of some subtle points.

I think of Ushahidi as two distinct entities which happen to be named the same thing... (1) the technology platform; (2) the people behind the organization who are dedicated to international development.

Much of the excessive hype around Ushahidi comes from people who think that (1) is the secret sauce and what offers a glimmer of hope for development. But, actually, it's (2) that makes Ushahidi great. It's people like Eric Hersman, Juliana Rotich, and Patrick Meier who are the real hope. It's their devotion to development causes that, for example, allowed Ushahidi's rapid set up for Haiti. (Even if the content wasn't ultimately of value to aid workers, it raised global consciousness about the relief efforts, as well as what was still needed. In fact, the Jester believes much of Ushahidi's positive value to date has been in raising public consciousness about certain global events.) Without (2), (1) would have been just another map mash-up tool, of which there are countless online. Technology (1) magnified the intent and capacity of people (2).

Paul Currion's key insight, though, is that for aid purposes, even (1) and (2) only go so far, because (3) is missing. And, what's (3)? (3) is human/institutional intent and capacity on the ground. As wonderful as Ushahidi (1)+(2) is, it makes no difference if there isn't (3), a force on the ground that can actually respond meaningfully to the noisy information (1)+(2) produces. In the case of Haiti, response teams were already overwhelmed. Additional information, per se, was adding to the unread mail.

This is a common lesson in ICT4D: Kiva.org is limited not by its technology, but by its microfinance institution partners on the ground. Government hotlines are limited not by call volumes, but by the quality of the response team. PCs in schools are limited not by their clock speed, but by the capacity of teachers to integrate them into curricula.

Bravo

All of this has been needed to be said for a very long time in regards to Ushahidi. They are playing with peoples' lives and this isn't something to be taken lightly. As a technologist, there are a few points that I want to follow up on at my site as they need to be addressed as well.

Anyone who takes issue with what you've written clearly doesn't understand what is at stake and/or directly benefits from the millions that Ushahidi has received.

good debate is needed

My 2 cents:

Surely harsh criticism and questioning are hard to take, but the debate here is really necessary because only by raising these points and seeing how they can be addressed can things move forward. Working with a foot in both areas, and as someone currently involved in implementing an Ushahidi instance, I think the points raised by Paul are valid and need to be addressed and thought through. I don't think that necessarily means that crowd sourcing and related ideas/initiatives need to be tossed out. But things do need to be continually evaluated and there is still much to learn and consider.

Having this kind of debate can enrich and improve on how new tools are developed and used, and I hope that Paul's points will be considered as people move forward with thinking, developing and testing new technologies. There is a lot to learn from past experiences. The points raised are not isolated. They reflect the views of many of my colleagues and friends working in the field of humanitarian aid, and so need to be considered and overcome by those developing technologies if the gap is to be bridged and we are to harness the potential of new technologies in a valid and useful way.

Linda

The game has changed

Thanks very much, as always, for your insights I find myself agreeing with nearly everything you have written, though I also, like others on this thread, hope and believe that your feedback will play a valuable role in shaping the evolution of these tools into something demonstrably useful in the future.

I remember a moment during Golden Shadow, a disaster simulation InSTEDD organized in late 2007 with California USAR TaskForce-3, when we used our early, hacked-together prototype of GeoChat to feed hundreds of scripted text messages (sent by community volunteers) onto the incident commander's map in the EOC. Over the course of the day, as the messages began to accrete, he went from mild interest to fascination. Then he got frustrated. He had simultaneously recognized that 1) he had never had access to this kind of information, 2) in aggregate, it was impossible for someone in his position to ignore, and 3) we had given him an "information firehose" but had failed to provide tools to "triage issues, create tasks, assign them, and track them to completion."

I do find it possible to imagine a day when what begins as an unkempt cluster of misspelled, unverified text messaages from God-knows-who ends up an "incident report" in an official emergency management system. We're still not there yet. Riff and Swift are examples of capabilities that could play a role in making that a reality, but much of what would be needed to siphon information out of the crowd and move it into the response coordination funnel does not exist, and has not even been imagined yet.

For Global Pulse, we are definitely interested in crowd sourcing crisis information, but the kinds of crises we're looking at are by and large slower onset emergencies. For us, we're looking to use citizen reporting as one of many inputs we can monitor for the purposes of anomaly detection. That is, we don't envision crowd sourced information as a trigger for response, but rather as a trigger for an investigation. We want use this information to know when we need to send out text messages to pre-identified trusted community members for preliminary verification, and ultimately when a team needs to be sent in to conduct a survey or assessement to GET the hard evidence needed to justify mobilization of large-scale resources.

Of course, this is a development challenge, not disaster relief. Real-time for us means on a time-scale of weeks (rather than months or years it takes to get actionable household statistics.) Disasters are different, and its about counting hours. Global Pulse can take its time and verify reports before recommending action. In a disaster, you have to make the call quickly: to which village do I send the truck first? The credibility of reports will be very low, and the price of mistakes potentially quite high.

One thing seems certain, though. Like it or not, this kind of information will be generated increasingly by disaster-affected communities, and it will be available to the global community -- including the organizations and individuals with an official mandate to coordinate response. These organizations may choose not to view the reports. Or they may choose to view them and then dismiss them as not actionable. Or they may choose to act upon them. Regardless, they will be held accountable for these decisions. The game has changed. We need to develop policies, processes and tools to deal with this information, because it isn't going away.

Wide variety of Crowds

There is entirely too much focus on a single technology. There is a very wide gamut of tools and capabilities that are able to leverage distributed, and often volunteer, teams. The technology, in my opinion, is clearly an enabler but always relatively easy. Tools have become sufficiently advanced to allow developers to do amazing things in very short time.

Another issue is not considering the array of volunteers. The crowd does not mean amateur. The World Bank convened hundreds of remote sensing "volunteers" to perform post-disaster assessment of buildings in Haiti. The group, GEO-CAN, utilized their professional tools, vast experience and knowledge to crowwd-source very accurate information.

CrisisCamps convened responders and developers to provide technical support and identified tool development such as support of wifi firmware modifications, Kreyol translation, knowledge portals, and surge support for projects such as OpenStreetMap.

I agree that there are concerns, and misinformed reporting on effectiveness in many tools. However, I believe also that the perspective has been too narrow in defining a large capability in volunteer crisis response information assistance through the perspective of a single tool or set of deployments.

Post new comment