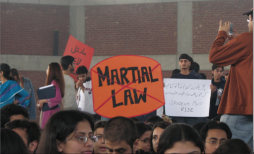

On November 3, 2007 Pakistan's President Musharraf declared a state of emergency and martial law in Pakistan, suspending the Pakistan constitution. During the next three months, during the short-lived emergency rule, Bhutto's assassination, and the general election in February of 2008, there was an unprecedented outpouring of citizen media, organizing and information sharing facilitated by new media -- blogging, mobile phones, and online video.

Huma Yusuf, an astute and eloquent journalist based in Karachi, has reported now on the convergence of old and new media during the 'Pakistan emergency,' as it is most often referred to in the country. It is a must-read document for anyone interested in citizen media, particularly in times of political turmoil, for the wealth of insights it provides on the current uses of digital media and the opportunities for future work in this area.

Her fascinating paper describes how students and activists used new media to organize each other, inform a public, and spread news and information through a confluence of digital media. She argues that during a time of political turmoil and censorship of traditional media outlets, Pakistanis turned to digital media and appropriated the various forms of blogs, SMS, Facebook, and You Tube to share and disseminate media. Yusuf notes how

"the media landscape became hydra-headed during the Pakistan Emergency: if one source was blocked or banned, another one was appropriated to get the word out. For example, when the government banned news channels during the November 2007 state of emergency, private television channels uploaded news clips to YouTube and live streamed their content over the internet, thus motivating Pakistanis to go online. In this context, the mainstream media showed the ability to be as flexible, diffuse, and collaborative as new media platforms."

She points to the importance of mobile technology and particularly SMS, and describes the multivalent flow of information from online citizen media to mass media such as cable television channels (in so far as those were not shut down) and the flow back of news from online and connected individuals to a broader public.

"A national "secondary readership" was established in a far more dynamic and participatory way during the Pakistan Emergency thanks to the prevalence of cellphones and the popularity of SMS text messaging. Indeed, this paper shows how citizen reporting and calls for organized political action were distributed through a combination of mailing lists, online forums, and SMS text messages. Emails forwarded to net-connected elites containing calls for civic action against an increasingly authoritarian regime inevitably included synopses that were copied as SMS text messages and circulated well beyond cyberspace. This two-tiered use of media helped inculcate a culture of citizenship in Pakistanis from different socioeconomic backgrounds. In other words, the media landscape witnessed a convergence of old and new media technologies that also led to widespread civic engagement and greater connection across social boundaries."

Yusuf describes in great detail some of the most interesting ways in which mobile phones were used during the emergency in new and unprecedented ways and eloquently described how, for the first time in the country, citizen journalists began to consider themselves part of a broader media landscape that had been dominated by mainstream media.

"The weeks during which all independent electronic news outlets were completely shut down or censored by the government marked a significant turning point in the Pakistani media landscape. It was in this media vacuum that other alternatives began to flourish: the public realized that to fulfill its hunger for news in a time of political crisis, it had to participate in both the production and dissemination of information. Activist communities established blogs and generated original news coverage of hyperlocal events, such as anti-emergency protests on university campuses. Civilians increasingly used SMS text messages to keep each other informed about the unfolding political crisis and coordinate protest marches. Young Pakistanis across the diaspora created discussion groups on the social networking site Facebook to debate the pros and cons of emergency rule."

Cell phones were, for example, used to call in 'traffic reports' -- reports of protests, street battles, closures -- and to radio stations that were then rebroadcast through public announcements. Radio stations had been prohibited from reporting hard news and had resorted to a widely understood code to instead report on 'traffic' that ostensibly obeyed the media restrictions.

Yusuf describes another, ingenious, way in which protesters had planned to disseminate information -- a plan well devised but circumvented by the authorities, illustrating the cat-and-mouse game that the protesters and activists played with the regime.

"On November 6, the ousted chief justice of the Supreme Court, who had been placed under house arrest when emergency rule was declared, chose to address the nation via cellphone. In his talk, he called for mass protests against the government and the immediate restoration of the constitution. Justice Chaudhry placed a conference call to members of the Bar Association, who relayed his message via loudspeakers. That broadcast was intended to be further relayed by members of the crowd who had planned to simply hold their cellphones up to the loudspeakers to allow remote colleagues and concerned citizens to listen in on the address. More ambitious members of the crowd planned to record the message on their cellphones and subsequently distribute it online.

However, most mobile phone services in Islamabad went down during Chaudhry's address, prompting suspicions that they had been jammed by the government. In the first few days of the emergency, sporadic efforts to cut telephone lines and jam cellphone networks were common, even though the telecommunications infrastructure in Pakistan is privately owned. Mobile connectivity at the Supreme Court, protest sites, and the homes of opposition politicians and lawyers who were placed under house arrest was jammed at different times. In off-the-record interviews, employees at telecommunications companies explained that the government had threatened to revoke their operating licenses in the event that they did not comply with jamming requests."

During the emergency, Pakistan saw a spike in SMS messages. SMS traffic had previously been relatively low in the country. Pakistan has high illiteracy rates and SMS is not available in local languages, slowing the adoption of text messaging. But traffic exploded during the first days of the emergency, indicating that SMS was a vital way for people to convey information and news of events, protests, rallies, and arrests to one another absent other independent news sources -- mainly television on which much of the country relies for news -- that were had been taken off the air.

Students and student organizers were particularly active during the protests in the early weeks. Yusuf describes how activists used a variety of reinforcing digital media to cover events. SMS blogs, mobile video, Flickrs and You Tube all were used to get the message out absent mainstream reporting. Because of the University setting, students were able to be online, updating blog links and tagging videos that had been produced with mobile phones throughout the day.

"Once students realized that major Pakistani news networks had not been able to cover their protest [at LMUS University], they took it upon themselves to document the authorities' intimidation tactics and their own attempts at resistance. Midway through the day-long protest, a student narrated the morning's events in a post on The Emergency Times blog, which had been established to help students express their opinions about democracy and organize against emergency rule. This post was then linked to by other blogs, such as Metroblogging Lahore, that are frequented by Pakistani youth. The Emergency Times blog also featured pictures of the protest.

Within an hour of the LUMS protest commencing, a Karachi-based blogger Awab Alvi, who runs the Teeth Maestro blog, also helped those behind The Emergency Times blog set up an SMS2Blog link, which allowed students participating in the protest to post live, minute-by-minute updates to several blogs, including Teeth Maestro, via SMS text message. Students availed of this set up to report on police movement across campus, attempts to corral students in their hostels, the deployment of women police officers across campus, and the activities of LUMS students to resist these actions. On the night of November 7, students posted video clips of the protest that were shot using handheld digital camcorders or cellphone cameras to YouTube. These videos showed the students gathering to protest, confronting the university's security guards, and the heavy police presence at the university's gates. Many clips focused on protest signs that students were carrying in an attempt to convey their message in spite of the poor audio and visual quality of some of the video clips. Anti-emergency speeches delivered by students were posted in their entirety.

It became soon clear, however, that the extensive use of digital media also posed dangers to organizers as arrests mounted. The security forces began to monitor Flickr, for example, and began to arrest protesters based on the posted photos. Students began to blur photos posted on Flickr and blogs in response, to avoid capture. Yusuf rightly notes that the fact that "the authorities were monitoring new media platforms such as Flickr is an indication of how quickly alternative resources gained influence in the media vacuum created by the television ban."

Yusif also notes how much savvier students were becoming as the protests continued, increasing the searchability of posted video and blog posts by better tagging to get their message out to international media and the Pakistani diaspora which was using Facebook to link and post videos and blogs.

Organizers also became better at using mobile phones for coordinating their protests as the emergency began its second month, indicating that organizing and citizen media training is essential to avoid such a steep initial learning curve.

On December 4, policemen and intelligence agents once again surrounded and barricaded the LUMS campus to prevent students and faculty from attending a daily vigil for civil liberties. As soon as police appeared at the LUMS campus, a post warning students that traffic in and out of the university was being inspected appeared on The Emergency Times blog. Once again, an SMS2Blog link allowed students protesting against the barricade to post live updates to the Teeth Maestro blog. This time, the live updates were used to identify particular members of the security agencies so that students could remain on guard and included messages from political parties advising students on how to conduct themselves during the protest. This content indicates that students were using them as a dynamic resource for community organizing during the protest, and not merely for archival and documentation purposes."

During the election in 2008, citizen activists again turned to digital media to monitor the voting process. A citizen coalition, according to Yusuf, enlisted 20,000 individuals to monitor polling stations. Voters and monitors used mailing lists extensively to keep each other informed and organized. Each email also included a mobile number, especially as election day was close, for coordination during the day. Email messages included a short summary that could be conveyed easily via SMS. Activists also used You Tube and SMS for inspirational video and short messages to encourage voters to go to the polls and alleviate fears of violence.

Even though the efforts were somewhat chaotic (as opposed to highly systematic and even scientific efforts by citizen groups such as recently in Kenya to monitor a statistically relevant number of polling stations and even conduct a parallel vote count), Pakistan had never seen such an outpouring of digitally-organized citizen activity to ensure a fair vote. On the day after the election, mailing lists and videos were again ablaze with reports from polling stations where irregularities had occurred.

Several videos of obvious vote rigging were posted on You Tube, prompting the security forces to block You Tube, and, in an embarrassing incident, managed to take the site down worldwide for several hours. This, in turn, created global media attention to the videos and allegations. Yusuf describes in vivid detail how old and new media converged, rebroadcasting videos from You Tube that then, in turn, gained the legitimacy in the eyes of regular Pakistanis that had been suspicious of the authenticity of the footage before seeing it on television.

Yusuf concludes with a tenuous but intriguing call:

"The sheer pervasiveness of new media platforms and digital technologies in Pakistan is leading to a situation whereby not only the digital divide, but also the participation gap, is being narrowed in ways that are unpredictable and unfamiliar, yet highly sustainable because locally relevant. An increasing awareness of such emergent uses of new media and digital technologies in the developing world might prompt the design and deployment of tools tailored to Third World realities, thereby facilitating participation, networking, and ad hoc community organizing in unprecedented ways."

I will be reporting more here on the tools and tactics specifically in regard to how mobile phones are used in media production and consumption, in citizen organizing, and emerging movements. I am looking forward on elaborating what Yusuf begins to call for in her paper.

To quote Henry Jenkins who is writing on PBS' Idealab: "Yusuf's conclusion suggests that the local conditions in Pakistan, especially in regard to mobile media, resulted in considerable experimentation and innovation -- born as much from desperation as from entrepreneurship -- in how new media tools can be deployed towards civic ends."

It remains to be seen whether this ad-hoc innovation can not be better harnessed during non-conflict times to be more readily available for when it's needed.

Meanwhile, go read her account -- it is a absolutely enthralling piece.

Photo courtesy rchughtai

Post new comment